|

|

|

| FOUR

- SEVENTIES Big Yank Lou Reizner was a strapping hulk of a man, bronzed and broad-shouldered, effervescent with that easy optimism that naturally infects Americans and equally naturally, bewilders the British working class, from whence I was begotten. Lou, proprietor of Reizner Music Inc, had gained an interest in me as a songwriter and travelled to meet me in Birmingham one summer's day in 1970. I picked him up from New Street station and then on the way to my moms house, he spotted a strange apparition: 'What is that?' he exclaimed. 'Hey Dave, pull over a minute.' I waited in my car outside a showroom for Reliant three-wheelers (!!) while, through the window, I saw Lou squeezing his giant torso into this, the archetypal conveyance of the English poor. It couldn't possibly have had any transportation interest to him, I imagine it was a jaunt of pure whimsy, an item of zaniness to turn up in at some Golders Green party. That day I played Lou all the good songs I had written and soon afterwards, I was invited down to his London offices to talk turkey: Lou lived in a sumptuous palatial residence in Kensington, right next to the cavalry barracks. The big ornate first floor room that was 'the office' had as its main focus an enormous carved wooden desk. Behind the desk, lay a patio window, and beyond, a balcony overlooking Hyde Park. All kinds of curios hung on the walls or stood poised in position around the room. A sword hanging in its sheath, an enormous globe gimballed atop its stilted bucket… I dare say each one could tell a tale of being held in regal hands, or of witnessing some august meeting of the rich and the powerful. Lou sat at his desk with the trees of Hyde Park swaying behind him while turkey was talked, and a deal was done. He signed me up as both writer and artist, giving me a handsome advance against my songs. Then after the shortest slice of time, I learned that he had produced an entire album of my songs with a British group called 'Wishful Thinking'. The album was to be called 'Hiroshima', the title of one of the songs. Lou had heard the scratchy demo I had done with Willy Hammond's help on my B&O recorder and zoomed in upon its simple message, but I have to admit I was enormously embarrassed to hear the finished version: Lou himself had done the voiceover, a repeat of the actual broadcast that reported to the world the explosion of an atom bomb over Hiroshima in August 1945. Shortly afterwards, Lou booked studio time (at Morgan studios, north London) to record an album of me singing my own songs. For a couple of weeks, while this was rehearsed and recorded, I stayed with him at his office-cum-apartment in Kensington. One day he came in from an appointment, installed himself solemnly behind his massive desk and addressed me with all seriousness: 'I've just been to visit my astrologer Dave, and she has told me that the things I am now working on - that means your music Dave - is going to have great success.' He studied my response, which was a puzzled 'Oh!' It hung in silence for a few seconds, like a pregnant question, for I had never before heard of such a weird thing. Someone with the power to divine the future… How strange it is to recall now, for indeed Hiroshima was by any yardstick 'a great success' and yet… Lou was a tower of virtue in the business of self-care. A picture of health, a pin-up for a body builder mag, had there been such a thing in 1970. It wasn't a surface affectation. I can describe Lou, without disrespect, as a complete health nut. Of course he didn't smoke or drink alcohol, in fact he drank only bottled water shipped in from abroad. He ate all the 'right' kinds of foods - strange stuff that I had never heard of. Nutty things floating in strange sauces, cardboard wheaty flakes that stuck to the roof of your mouth, to be washed down with the inerrant juices of some obscure, but healthy vine. (Dinner time was a pinnacle of torture for me, there were no beans on toast or chip butties to be had staying at Lou's place). So when Steve Wheate brought me the newspaper cutting reporting that Lou had died after a short illness in November 1973, I found it especially unsettling and shocking, knowing so well the priority he set on things that should have guaranteed his eminent longevity. The song ‘Hiroshima’, which Lou had spotted and made the flagship for the Wishful Thinking album was indeed enormously successful, becoming a European hit not just once, but twice. But the Big Yank who had first nurtured it - and me, was never to partake of its success. Folk Singer The advance from Lou enabled me to buy a ticket to the United States where magically, a career as a folk singer began to unfold the very first day I ever set foot on American soil. But in order to tell you about America, I have to tell you about Turkey first. Yes, you are right, that is the wrong direction completely, but that's rock 'n' roll. Really, it was only going to the land of Caliphs and Minarets that enabled me get to America. Let me explain... I was with a group called 'Blaises' and for three months in early 1967 we were resident in south-east Turkey, playing five nights a week at the giant US Air Force base called Incirlick - where Gary Powers had taken off on his fateful U2 spy mission in 1960. |

|

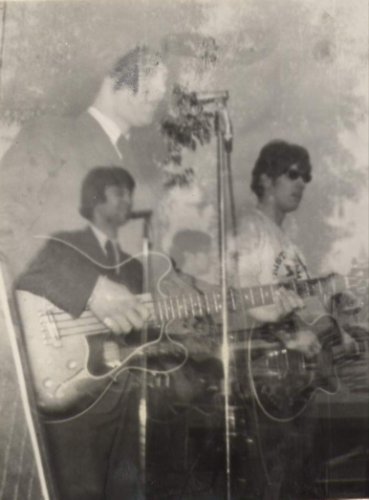

Blaises, Turkey 1967 Double exposure 18 March 1967: An open-air show which was televised across the base |

Playing at the NCO club, Incirlick Air Base, Turkey. The drummer is Keith Smart. |

|

One night we were playing The Officers' Club when a lady caught our

attention from the platform - she was easily the most sparkling and

vivacious lady on the dance floor: 'See that bird there?' bass player Bob whispered to me while we were playing. 'Yeah, she's mine, lay off' I giggled back. 'Oh yeah?, we'll see about that.' In the break a man came up and complimented me on the way I sang the song 'The lady is a Tramp'. 'My name is Joe Corcoran' he said, 'come over and have a drink with us.' I walked across the dance floor to his table and was introduced to his wife. It was the 'bird' we had been ogling (!!) 'My name is Turkan' she said, explaining that she was in fact Turkish, 'but everyone calls me Corky.' Close up I could see how her stunning features had discounted her age, which was only thirty plus, but then, when you are as I was, twenty plus, anyone beyond the next magic threshold inhabited the realm of moms and aunts. I became a regular visitor at the Corky residence in the nearby town of Adana. We became good pals. Yes, pals- don't get any ideas! Although she was beautiful, Corky was always like a surrogate mother to me. The following year while she was en-route back to America, Corky and her daughter Deniz came to spend a day with me in Birmingham. Before she left, she extended an open invite for me to stay at her home in Glen Burnie, Maryland - if I could ever afford the ticket to get to America, that is. And so in the autumn of 1970, after recording the album of my songs with Lou Reizner, I found I had both the appetite and the money to take Corky up on her offer. I landed at New York's JFK airport on 30 October 1970, wide-eyed and jet lagged and carrying an acoustic guitar in a leatherette bag. Waiting for the connecting plane I struck up a conversation with the then-unknown group 'Black Sabbath', who had heard my Brummie accent at the check-in desk. We travelled together to Philadelphia, a stop on the way to Baltimore. I had never met them before, although they were from Birmingham. Corky was waiting to meet me at Baltimore airport with an enormous welcoming smile and expansive hugs. After installing me in my own room at her house ('boy, my own room! - I never had my own room at mom's house in Tile Cross' I thought!) she drove me around the 'sights' of Glen Burnie and we popped in to the local shopping mall. That's where I met George Richardson, the effervescent manager of one of the shops: 'Oh so you're Corky's friend - Oh, you met in Turkey and you're English, Oh - Wow! - AND you play guitar! - Hey, I run a coffee shop here in Glen Burnie. Why don't you come down?' He seemed to be describing something other than a retailer of coffee beans, but I'd never heard of the expression - 'What's a Coffee shop?' I asked. 'Oh you know, a place where we all sit round and play music' he replied in the easy, silver manner of the salesman he was, adding that 'tonight' was 'coffee shop' night. That was how I got to be performing in front of people the very first day I was in America. I played a few songs - some of mine and a Dylan song 'Just Like a woman.' It went down so well I became a regular at George's Coffee shop before branching out for new horizons. |

|

| Corky was waiting to meet me at Baltimore airport with an enormous welcoming smile and expansive hugs. After installing me in my own room at her house ('boy, my own room! - I never had my own room at mom's house in Tile Cross' I thought!) she drove me around the 'sights' of Glen Burnie and we popped in to the local shopping mall. That's where I met George Richardson, the effervescent manager of one of the shops: | |

|

'Oh so you're Corky's friend - Oh, you met in Turkey and you're English,

Oh - Wow! - AND you play guitar! - Hey, I run a coffee shop here in Glen

Burnie. Why don't you come down?' He seemed to be describing something other than a retailer of coffee beans, but I'd never heard of the expression - 'What's a Coffee shop?' I asked. 'Oh you know, a place where we all sit round and play music' he replied in the easy, silver manner of the salesman he was, adding that 'tonight' was 'coffee shop' night. That was how I got to be performing in front of people the very first day I was in America. I played a few songs - some of mine and a Dylan song 'Just Like a woman.' It went down so well I became a regular at George's Coffee shop before branching out for new horizons. |

|

|

The horizon that beckoned was in a

southerly direction, and I was propelled toward it by a girl I had met

(a 'dizzy broad' Corky called her disapprovingly!). Sharon had in mind

toasting herself in the Florida sun and away from the freezing Baltimore

winter of January 1971. Together we planned a way to get to the sun via

the auspices of a drive-away car (that's a car whose owner has jetted on

ahead leaving it to be delivered to him. Only in America do such things

exist it seems). Just north of the city of Miami, in the coastal town of Fort Lauderdale, a little motel caught our eye: the 'Riptides' it said proudly on the high gaudy neon sign. We pulled in and rented a room. That evening I found myself

sitting around the pool beneath the mild tropical winter sky of Florida,

strumming my guitar while the motel manager and a couple of other young

guys listened. The manager immediately telephoned a friend of his - Ron

- who had a late night show on a radio station in Miami (WBUS - 'Magic

Bus') and got me to sing down the phone to him. Miami |

|

|

|

|

|

The 'Bird' looked like an American

version of Confucius, his spindly frame animated with an elastic swagger

bedecked by an ever-ready, knowing smile. Before he had left the studio

that night he had offered me a place to stay and in a short order I had

moved in with him, becoming the beneficiary of his home, his Volkswagon

car, and really everything he had - except his girl-friends of course. I

had entered into the pot-smoking hippy culture of America, where

everything was communal property. Somehow, I don't recall just how,

I became hitched up to a local music impresario named Steve, and through

him, I met up with a singer named Mickey Carroll. When we met, Mickey

was sat with two other musicians high up on an elevated balcony

overlooking the bar at the Rancher Motel, Miami, singing and smiling

down at us through his Don Juan moustache, while delivering a Vegas

ambience of musical cool.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Looking Glass I ended up spending a year and a half in America in two visits separated by a short spell back in England in between. On both trips I played with 'The Looking Glass.' I also appeared as a folk singer

but I have to admit I was not wonderful at it. At one place I got booed

off. Mind you, the crowd were waiting to see Eric Burden - the next on

the bill - at the time. A roomful of seething rhythm and blues fanatics

were greeted by Moi, with feeble acoustic guitar and wobbly voice and

they were not amused. It was what you might call a tough assignment. |

|

|

The Looking Glass 1971-72

|

|

|

Rum

Runner As I became a regular visitor at the Rum Runner, I got to witness Albert’s rules in action many times: Often this would take the form of a rugby scrum surging through the labyrinths of the club - Albert and his crew motivating a ‘trouble-maker’ toward the exit like an army of ants would roll a piece of bread toward their nest, the crowd parting before them like the Red Sea as they inexorably progressed their quarry toward the entrance, and the final resting place of all ‘trouble-makers,’ the cold cobblestones of the alleyway beyond. I had worked

at the Rum before, for four months in 1970 as part of the resident

group, ‘Fred’s Box’ (just before recording my album with Lou

Reizner). Through my

frequent visitations to the Rum Runner, I got offered a job with the

other musicians as a labourer at the pubescent ‘Snobs’, a prospect I

promptly said ‘yes’ to, being in need of the cash at the time. I remember

the day that Kex found his brand new boots had been pinned to the

concrete floor of our makeshift changing room with an industrial gun,

and the fact that the same device was used later to nail someone into a

toilet (I don't remember who it was). I became pals

with Tony Clarkin, the lead guitarist of ‘Fred’s Box,’ during that

stint as a labourer. It was really the genesis of the heavy-metal group ‘Magnum,’ who were later to sell many tens of thousands of records and become a cult hit amongst Christendom’s head-bangers and leatherwear rockers, under the propulsion of Tony’s great songs and guitar playing. But back then they were still just a resident group at a nightclub, playing the flaccid hits of the day and being perpetually told to turn down because the waiters in the restaurant couldn’t hear what the customers were saying to them. Mick |

|

|

|

|

|

Nothing Says The first time you hear a great song can often be a moment frozen forever in time. It is also the instant you really know how good the song is. That's the thing about the first time, it's a point of ultimate revelation: The time you know that there is nothing so beautiful as that you have seen, and long to see again. There are many Beatle songs, which stopped me in my tracks when I first heard them. 'Eleanor Rigby' is one; I first heard it when I was driving through the centre of Birmingham in my Jag. I pulled over, parked up and listened to it, mesmerised. To me it was just enchanting and beautiful. Long after it had finished I was still transfixed in a stupor, just wishing to hear it again: 'All the lonely people, where do they all belong?' Many years later, in 1976, another great song came to visit upon me not from the speaker of a car radio but from the proverbial 'horses mouth' as it were, sung by its creator and custodian, a rotund bearded Irishman named Jim Cleary. I was visiting a pub in Moseley village, Birmingham and Jim was one of a three-piece group playing to the packed room. One of the songs they performed that night was 'Nothing Says' and instantly, like 'Eleanor Rigby,' it was a slice of music I just wanted to hear again and again. It glowed with a timeless circular message that came through loud and clear - Nothing says goodbye like a tear - but the musical pirouettes it danced around to transport that message was, upon first hearing, a pure enigma to me. Jim had a way of honing chords that confounded any rules of music I knew about. After meeting him and hearing more of his songs, I soon discovered that 'Nothing Says' was not a fluke or a one-off, but just one of a whole series of devastatingly original songs by Jim. I was instantly jealous and conspired to be in a group with him, maybe to discover where he kept his vial of secret tunesmith unction and yes, to steal a bit of it if I could. I fast became privy to Jim's Irish proclivity for Guinness - with or without a whiskey chaser, depending on the position of the sun over the yardarm - and for a while I thought maybe the secret unction was in that, but of course it wasn't. It was in places I could never reach - growing up in the streets of Dublin, migrating with mom and everything you can carry onto the Holyhead Ferry and the promise of prosperity in Birmingham, and finally the fine halls and finer verbiage of the University of Birmingham to buff and polish the rich tapestry that the university of life had already given him. I was to spend many happy hours in the company of Jim's effervescent banter: the whiff of the Blarney mixed as it was and still is, with his studied Etonesque vocabulary imbibed from his University days. We became pals and before too long I had teamed up with him as 'Morgan Cleary', first as a duo and later, as a trio with the addition of lead guitarist Bob Daffurn. During 1976 we were playing local folk clubs and pub sets in and around Birmingham. Then in the autumn of '76 Richard Tandy breezed back into Birmingham from his globetrotting travels with ELO. He called me to say that he was able to get studio time to record me with him producing, and did I want to make an album?… 'Wow Rich - Yes! But er…' Richard had never heard of Jim Cleary and was a little taken aback when I tentatively proposed the album be of Jim and me instead of just me, but after hearing Jim's songs (I think we sang them together in the sitting room of his Moseley flat), Richard was soon sold on the idea. Studio dates were booked at DeLane Lea studios in Wembley, North London, and during November and December of 1976 we spent seventeen days recording twelve tracks for an album produced by Richard Tandy for Jet Records (Don Arden's label, made recently rich by ELO's successes). Under Richard's aegis, we were swept up to unheard-of levels of swish: We were chaperoned to London in a big Ford car driven by Upsy, booked into a proper hotel instead of one of those seedy Bayswater bed and breakfast places with beds you were reticent to lie on and toilets you were scared to sit on. And the place itself - DeLane Lea - this was not built like an adjunct to somebody's shed as we were used to - No, it was a proper recording studio, the best I had ever seen and one I believe that ELO had previously used. At any rate, I remember Don Arden's office had an account with them and picked up the tab (or do I remember it because they didn't pick up the tab? It's one or the other…) Yes it was a side of the music biz where the grass was definitely greener and Richard was eager to show it to us and to broaden our vista a little toward the glad hand of fortune that had broadened his so generously. There, with a proper sound engineer, we laid our souls bare before proper microphones wearing proper stereo headphones. No expense was spared. If josticks and camel sauce be ordered along with fish and chips then God forbid the roadie to come back without it as specified. Steve Wheate came down to help us with drums and Jim Cleary entertained us magnificently with his Irish caricatures, quips and beer cans, and when they ran out and Jim fell spark asleep one night, we bound him from head to toe in gaffer tape as he lay on the studio couch and then denied all knowledge of it when he woke up snorting like a polar bear in his straight-jacket truss several hours later. But all that glitters is not necessarily the source of the Nile and the end of the story is that our finished album was never released. It languished somewhere in the vaults of Jet Records, my six songs and Jim's six - for a short while the toast of the town, but thereafter condemned to be orphans of unknown whereabouts. The end of the recording sessions, marked also the beginning of the end of the Morgan Cleary group. Show business is both a 'show' and a 'business' and in it you oscillate between the two. So our show ended and our business began with talk of deals flowing between London and Birmingham like pieces of paper blowing on the wind. Somewhere beneath the paperwork and ever more mystical promises of Jet Records, our little ship capsized and slowly sank along with our dreams of hit albums, or even released albums. At any rate Morgan Cleary didn't last too long after DeLane Lea. And when it was finally ended it was all I could do to get the disappointment out of my system and roll it all up into a song called 'Princeton' (and I suppose in some weird way the University town signified a place of discovery, like we had stumbled upon the secret of how to build a new particle accelerator or something. But really I was just thinking of Jim's wonderful music and Irish prose, his lepricorns and space ships and the planets they took us to, the sheer magic of it all). Anyway 'Princeton' was my message to the cosmos, a swan song in memory of our little group which I loved dearer than any woman. But back to Jim's song… Nothing says goodbye like a tear and nothing says hello like a smile. Yes it was burnt into the oxide at DeLane Lea but I have to say it never quite recaptured that magic I had first heard in Moseley, never quite made it back to the summit, and that crystal-untouched snow. For me, somehow the picture was overlaid with the slushy footprints of our exertions. But like an inconsolable lover, the song would not let me go and years later I had yet another go at it. In 2001 with Jims permission, I did a version of it and released it on my 'Reel Two' CD. |

|

|

with Jim Cleary

|

|

|

In

1977, I was living with Sheila, in her house. Sheila worked, I didn't. I

stayed at home composing songs and working on projects, a bohemian

freeloader full of promises but without the wherewithal. The

young girl behind the grill said the same as before: The

Claimants Union didn't look like much, but that black lady sure knew her

stuff. | |

| All photographs are copyright David Scott-Morgan unless otherwise credited. |

|