|

|

|

|

THREE - BIRMINGHAM BLUES

The City of Birmingham in the mid sixties was a landscape alternating between the scars of German

bombs and the grimy Victorian edifices that marked its industrial

heritage. Nestling in its underbelly, just outside the heart of the city

centre, was the Cedar Club. It had all the attributes of an Al Capone

speakeasy: A dingy frontage looking every bit from the outside like a

brothel lit by candles, with windows emanating a muted reddy hue around

gaps in the curtains. |

|

|

|

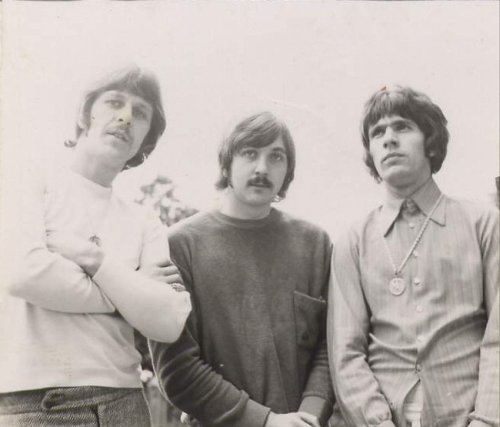

Left: Danny

King & Trevor Burton 1966, |

| Germany Danny King's group sort of fell apart when the organist got arrested at a gig one night… There was something about stolen equipment being found in his inventory. Anyway, shortly after the dust had settled from that fracas I joined a group called 'Blaises,' an attempt at putting together a local super-group by manager Arthur Smith. The local scene however, was soon mercifully released from 'Blaises' as they were extracted out of it and sent to Germany for a month. After all, the Beatles had shown that a stint in Germany was the way to mega-success… Our group transport was an old ambulance recently retired from service. It was more like a baby charabanc with windows along the side, big comfy seats, and a sleepy soft suspension that imbibed an undulating motion as it trundled along, making it feel like you were travelling on a motorised water bed. On the ferry crossing from Dover to Calais the Captain of the ship - a stern looking Danish man - took exception to the Ambulance sign still displayed in a lighted vent in the roof of the cab. He gave us a tin of white paint and ordered us in broken English to paint it over before he would let us off his ship. He must have dropped out a word about our unsociable presence to the Gendarmes at Calais because they promptly impounded us, and our ambulance - locking us inside a giant shed for several hours before repatriating us back to England on the same ship. We spent the night in our ambulance on the car park of Dover docks and the next morning booked passage on a ferry to Ostend. We hoped the Belgians would be more obliging to us than the French had been, and they were - they let us in without mass arrest, imprisonment or even the suggestion of garrotting anyone. Our invasion of Europe finally secure, we set course in a somewhat humbled fashion for Germany, undulating our way across the motorway system through the day and night to arrive at Hannover very early one morning. We found the club where we were booked to play - the Savoy - and looked at it in horror. It was a dump, an old converted cinema, with gaily coloured posters pinned to battered, shabby walls of peeling stucco. We peered through the grey dawn at the scene before us and, in our slightly comatosed, half-asleep condition, made daft jokes about it. Raucous laughter ricocheted through the ambulance as, surveying the state of buildings adjoining the club, one of the group pointed to a desolate outhouse with bars at the windows and said: 'Hey look, there's the hotel where we're staying at.' Some time later a cleaner came and let us into the club. We were shown to our quarters - they were the adjoining outhouse we had all been laughing at. We played at the Savoy in Hannover for three weeks, five spots per night, sleeping and living in the concrete bowels of our 'hotel' which had a star rating lower than Colditz. The organ player broke his leg, the singer caught crabs and the drummer had his leg bitten into by a German girl after an enormous fight broke out in the ambulance as we were taking some girls home one night. After Hannover, we moved to Brunswick for a week – or Braunschweig as it was rendered in the native tongue. We played on a stage that was about three foot wide and fifty foot long - All stood in a line sandwiched against the wall, like suspects in a police line-up. Across the other side of the club, behind the bar, stood the proprietor: An enormous portly German with a playful, slightly psychopathic manner. He developed a penchant for conducting us from where he stood across the room, employing a system of easily understood hand gesticulations intersperced with a show of his ample knuckles and his best expression of menace. That was the way he would tell us to turn down. Using this orchestral semaphore system, one night he gradually lowered the volume of 'Blaises' until we were turned completely off! - the drummer was tapping gently on the sides of his drum, the singer was just whispering and the only other sound to be heard in the club was our plectrums strumming across dead strings. All our eyes were glued to the owner as he beamed child-like, head raised to the ceiling like a music lover lost in rapture. Then suddenly he recomposed himself into a glare of Wagnerian anger, his jaw sticking out and his face contorting into a raging passion as his hands rose up from the bar-top motioning us to increase the volume... Bit by bit, with hands and fists, he had us get louder.. and louder, and louder, and louder, and even louder still! - Until the noise in the little club was excruciating, and we were thrashing our instruments like drunken dervishes while he stood like a warrior king on a hillside, his arms punching the air in a rage of victorious ecstasy. Yes he was quite a character. 'Blaises' came back from Germany and later went to Turkey before folding in the late spring of 1967. But more about that later… |

|

|

Ugly's ’What?’ mom said horrified, when I

told her I was going to join a group called the ‘Uglys.’

|

|

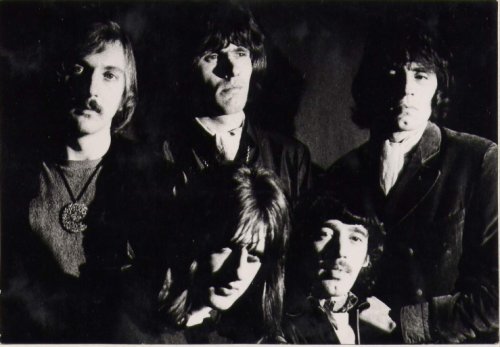

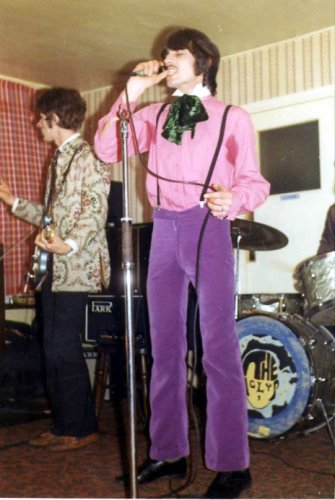

The

Uglys

1967-68.  Below playing at 'The Station' in Selly Oak. From left: Willy Hammond, Steve Gibbons, Jim Holden, myself. At right is an earlier version of the Ugs with me on rythmn guitar. |

|

|

|

|

The ‘Uglys’ were a one-off.

Steve was, and still is, a most colourful and charismatic performer with

a wonderful voice and a way of expressing himself visually that then,

and now, is a treat to behold. I always thought he had ‘star’ written

all over him, but Steve was to make only one incursion into the British

hit parade, in the late 70’s, with the Chuck Berry song ‘Tulane.’ Such

is rock ‘n’ roll.

The pie stand had closed early for some reason. We looked out of steamed up car

windows at its deserted facade in despair.

‘Oh no, I’m starving. What’re we

gonna do?’ someone said. ‘Yes you can,’ chuckled Charlie.

‘Just watch me.’ Yes it was the age of being

gloriously and outrageously silly. Charlie had a different take on glory

to me though, and one of the more outrageous things he used to do was to

smash up a television set on stage: I thought having a Beatle haircut

was revolutionary, but destroying a television set? Surely there must be

a law against that? – Isn’t it sacrilege or something? Well of course, it meant that the ‘Move’ were bent upon moving up and out of Birmingham; the Midlands; anywhere remotely provincial, and stepping up into the centre stage of our universe – London, the capital of the music world. With the help of their new manager, media locust Tony Secunda, Charlie had set the Move on to a trajectory that would make them a household name. It was a fact that unfolded before our Brummie eyes. And in between these goings on, we recorded loads of my songs, mainly at my mom’s house. Charlie was an honoured visitor, one of the few amongst my musician pals to gain moms unreserved approval. She’d make sure the table cloth was clean when Charlie was coming to visit, and he always paid her special attentions too. We never spent a long time on the recordings. It was never a job, always something like: ‘I’d like to play that song to somebody Dave. Let me have a tape of it.’ And me replying: ‘Oh, I don’t have a decent demo of it yet.’ And Charlie would say: ‘Right, I’ll pop around at so-and-so time and we’ll record it.’ That was the way it happened. I would be frantic with care about every syllable and crotchet but Charlie would just turn up and sing my song, and in three minutes it would all be over. Mom would make a cup of tea and be fussing all over him while I was scribbling the name of the song on a tape box, with a note that Carl had sung it. |

|

|

Something I had been trying to compose an entertaining song with a nice simple tune and I came up with ‘That Certain Something'. Unusually for me, it wasn't written for anyone or anything in particular, it was just about the flow of life; - the search for that certain something that you can’t describe, but like Steve McQueen said in the horror movie ‘The Blob’ – ‘you’ll know it when you see it!’ I played it to Charlie on guitar and he picked up on it straight away, shortening the title to ‘Something’. Then in the summer of ’68, Charlie told me he was going to do it with the Move. They recorded it with a string arrangement (a new departure for them) and by November, it was a toss-up which would be the A side for the new single release – my song ‘Something’ or Roy Wood’s ‘Blackberry Way.’ |

|

|

On 13 November, Charlie and I were in London,

at the offices of ‘Galaxy’ - Don Arden's management company. Don Arden

was the Move’s manager (Tony Secunda was manager when they became

famous, but now we are a little further downstream). Don was a short

stubby man who seemed to revel in promoting his legendary renown as a

gangster – you could call him ‘The Don’ and he wouldn’t get offended.

The godfather angle was probably good for business! I don’t know if Don took notice of my advice but the fact is a few weeks later ‘Blackberry Way’ was climbing up the charts, and by the following February, it was at number one. My song was on the B side and that was good for me also, at least financially. The publisher gave me an advance of £500 for it, a small fortune at the time. I remember I banked it and then withdrew the lot in cash so that I could go and open a new account closer to where I lived. Coming out of the bank I dropped the lot in the street. It was like a scene from ‘The Gold of the Sierra Madre’: I was on my hands and knees in the road, eyes bulging with avarice, competing with the wind for dominion over the rebellious green tablets trying to make their escape down the Washwood Heath Road. |

|

The Cedar Club 1968: Trevor Burton, Richard Tandy, myself and Carl Wayne. |

|

|

|

|

|

The Move recorded one further song of mine: ‘This Time Tomorrow’ but before that was to happen, other dramas came into focus: Trevor Burton and drummer Bev Bevan got into an argument one night while

they were on stage in Germany. According to how Charlie related it to

me, Trevor threw his bass guitar at Bev. Now Bev is quite a muscular

bloke, and when he stood up and grabbed the nearest weapon to hand – his

side drum which Upsy, the roadie, had nailed to the stage to stop it

moving, he picked it up with such venom that the stage planking came up

too. He then proceeded to project the whole rig with due vigour at

Trevor. The crowd thought it was all part of the act and they cheered

and whooped with delight… Meanwhile as the two disappeared off stage,

chasing each other with various items of furniture, Charlie and Roy were

left to continue the song alone, and when the curtain fell that night,

that was the end of the Move with Trevor Burton in it. I had been with Steve Gibbons

in the ‘Uglys’ for eighteen months and I liked playing with the Ugs. To

complicate matters, my mate Richard Tandy had just joined on piano and

Steve had told me that there was even talk of Trevor Burton now joining

us (!!) and of the group being re-formed and going for the big time in a

completely new direction. The upshot of all this is that Trevor Burton did indeed join the ‘Uglys’ - as the lead guitarist. Willy Hammond got sacked to accommodate him, and under Trevor’s input and influence, Steve had agreed that the group would have a new manager, Tony Secunda. I winced when the news came in. I had escaped the net of Don Arden only to be caught in the snare of Tony Secunda, himself a legend with his aggressive confrontational style (He once devised an advertising campaign which implied that the Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, was having an affair. The ensuing legal battle cost The Move all the royalties to a top ten hit). But by now I couldn’t back out. The job with the Move had gone to someone else (Rick Price). When you’ve made your bed you’ve got to lie in it. Being sacked from the Uglys was the best thing that ever happened to Willy Hammond. He went off and joined the Air Force and this led to a distinguished career in the foreign office, with many adventures of international gravity, the substance of things that set the exploits of the entertainment business into dim insignificance.

The new group with new direction, new ethos and new manager, needed a

new name. Needless to say with Tony Secunda involved, it had to hit you

square between the eyes, and if it could be inflammatory too, so much

the better. The new banner was unfurled and I found myself in the group

named ‘Balls’ - the most aptly named group I have ever been in. It was a

disaster from the word go. |

|

|

The

Dish. Jimmy

O'neill (centre) with Steve Gibbons and drummer Jim Holden |

Mary Colinto - Jim's

sister Kathy O'neill.

... the title of a song I wrote in 1968 which became a sort of local hit, played by many Birmingham groups. It was recorded by the Ugly's for the CBS label but not released due to the group disbanding to form Balls. |

|

The Birmingham group scene had

ways to deter anyone from taking themselves too seriously. It was all to

do with the way you presented yourself, or were presented by others. An

‘unearned’ or artificially enhanced notoriety could result in you being

labelled as ‘flash,’ which was akin to having a notice board strung

around your neck warning that you carried a communicable disease. Yes,

the Flash Squad was ever on the prowl to bring you back down to earth...

Some time later Jim left the

Walker Brothers and moved back to Birmingham to become a long-standing

member of the Uglys. |

|

|

Swedish Baroness And then there was Gabrielle, the Swedish baroness, exiled from her inheritance to live amongst the commoners of Birmingham – in the suburb of Rednal in fact, where she worked as a seamstress and made all the clothes for the Ugly’s. Ah, how she entertained us with her Nordic accent and fine sweeping movements of her slender frame as she modelled her psychedelic garments and wove her dream of one day being repatriated to the beautiful snow-capped mountain redoubt, the castle and the family heirloom, all hers by right and you’d better not doubt it, stolen from her by wickedness and subtefuge. And later, much later, how we learned incredulously that she was neither Swedish nor baroness, and this fact along with her true accent (which turned out to be as common as ours) were laid upon us like the sodden plot of some bar-room play. Yes Gabrielle was one of the characters who made the sixties what they were for us, a voyage of pure discovery on the good ship Whimsy. |

|

|

|

|

|

Balls Balls

lasted for one whole month. For me it did anyway. The group was formerly

inaugurated on Monday February 3 1969. It was a heady time all round.

Just two days before I had been offered the job of playing bass guitar

with The Move. On that day they were Number 4 in the UK singles charts

with ‘Blackberry Way’, with my song ‘Something ‘ on the B side. Carl

Wayne wanted me to join his group and he didn’t like the idea of me

going off with Trevor and Tony Secunda. He had even arranged a flat at

Streetly (a very posh area North of Birmingham) where I could shack up

and write songs in peace. I had made the decision to stay with Steve Gibbons and so I moved down to Fordingbridge. It was a special place - New Forest Donkeys came roaming in the kitchen of the little wooden bungalow that was our humble habitation and flagons of country cider were a standing order on shopping day. I drove back to Birmingham one Sunday in late February and called Carl. He announced to me that he wanted to record a song of mine called ‘One Month in Tuesday’ (which went by the affectionate nom de plume ‘Corky’ on account of the fact it began: ‘Corky wrote today…’). I called Trevor to tell him this - for me, good news. He was hopping mad about it, suggesting that Charlie was up to no good. I spoke to Charlie again and a little later he called me back to tell me he had called Tony Secunda, and there was no problem at all about him recording one of my songs. Secunda was strangely and uncharacteristically ambivalent it seemed… When I returned to Fordingbridge on Monday, I learned that Trevor had left abruptly for London after the phone call the day before. He re-appeared with Denny Laine late on Tuesday the 25th and the two of them didn’t have very much to say but I remember they did play all night at a very loud volume. Just why Denny Laine had come along, seemed to have sinister overtones to me, and the next day, I spoke to Steve Gibbons about it. He didn’t know why he'd come either and was bothered about it himself. It seemed to portend a change of line-up… We both decided we needed to speak to Trevor about but when we did, he flatly denied that any change in the group was afoot: ‘Absolutely not’ Trevor said, shaking his head. ‘Denny is just sitting in with us because his thing has fallen through in London.’ He was quite emphatic about it. Steve and I were re-assured. The new super group lurched on for another week. Rehearsals were, I guess I would describe them as undisciplined. The music was almost exclusively interminable 12 bar blasts that went on for hours, the archetypal rock n roll groove. I didn't much like the groove and I didn't much like the politics – increasingly there was a pervading atmosphere of intrigue around the place. Then on Tuesday 4 March, Trevor and Steve Gibbons took me to one side. Trevor said to me: ‘This band aint happening!’ I felt a certain relief to hear that. At last somebody had put it into words. He continued: ‘…and er… We have decided that er… you, - that is you and er… Richard… well.., you don’t fit!’ That was it. I looked at Steve.

He wore a grimace of resigned displeasure, like somebody who had signed

up for the parachute regiment and now wished he hadn’t. But it was too

late. I baled out immediately and I

think Richard left the next day. |

|